In 1988, for the thousandth anniversary of Christianity in Russia, I had the joy of leading a tour to Scandinavia and the Soviet Union, entitled “From Trolls to Icons.” I didn’t know then that the encounter with icons would so fascinate me and that after an almost mystical experience I would become a student of icons myself.

Inspired by what I’d seen on the trip, I decided to write an icon of St. Luke writing the first icon of the Holy Theotokos. I placed it on a wall in my study, along with several reproductions of other icons, to form a worship center for my daily prayers. Not satisfied with my own, I thought about buying a “real” icon. I went to the bookstore at St. Vladimir’s Seminary in Crestwood, New York, where I found what I thought was an icon very similar to one I had seen on the tour. Although it was beyond my means, I seriously considered purchasing it. When I returned to give it a second look, an Orthodox priest came by and asked if I was thinking about buying it. When I said yes, he informed me, “This icon looks like an icon but it really isn’t an icon. It wasn’t painted according to the traditions of the Russian church since the artist used acrylics and not egg pigments and probably smokes cigarettes and drinks beer.”

Not long after this, a member of my former parish in White Plains who knew about my efforts gave me a New York Times article announcing a class in icon writing at the School of Sacred Arts in nearby New York City. My interest sparked, I began to consider whether I should enroll. It so happened that while I was thinking about the class, I was also trying to quit smoking. One night, I had the most vivid dream in which the Archangel Gabriel appeared to me saying: “Fred, for fifteen more years you are going to serve your parish, but when you retire the Lord wants you to go to St. Catherine’s Monastery in Mt. Sinai and become an iconographer.” I asked, “Why me?” Gabriel said, “Because my icon painters are not faithful; they paint in acrylics, and while they paint they smoke cigarettes and drink beer.” I remember also saying, “But Lutherans are not iconographers.” And he said, “There always has to be a first.”

I woke up in a sweat. I knew the conversation with the priest and my wrestling with smoking probably had something to do with the dream, but I did decide to take the class anyway. It was one full day a week for twelve weeks, taught by Vladislav Andreyev, a Russian-born iconographer who had emigrated to the United States in 1979 and would later become the founder of the Prosopon (“Face”) School of Iconography. Later, I would take private lessons in his home and have him conduct two eight-week courses at my church, where more than thirty members and friends of the congregation studied and wrote icons.

Even before I studied with Vladislav, I knew a little about the iconoclastic controversy of the mid-eighth and mid-ninth centuries. At issue was whether, in light of the Old Testament prohibition against graven images, the church could paint and venerate icons. The resolution approving icons was based mainly on arguments from Scripture, early christological formulations, and the writings of John of Damascus. Since God revealed Himself in the second person of the Trinity with a human face, that face and the faces of the saints could be painted. The honor shown to the icon was truly given to its prototype, not to the icon itself. Two of my favorite Scripture passages in support of icons are our Lord’s own words to Philip, “He who has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:8–11) and Paul’s words, “He [Jesus] is the image of the invisible God… For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell” (Colossians 1:15–20). I also knew that icons were painted on wooden boards and remarkably beautiful, and that churches of the Eastern tradition lavishly filled their worship spaces with them. But I was soon to learn much more.

Shortly after entering Vladislav’s classroom, I knew that smoking and icon painting did not go together. The painting of icons was a spiritual discipline. Every class began and ended with prayer. In the painting process, I was expected to call continually upon God to guide my thoughts and hands as I went through some twenty stages in writing (not painting) an icon. Vladislav pointed out that the secular artist paints using an easel with the canvas vertical and reflecting the artist’s perception of reality, himself, his imagination, and his creativity. By contrast, the iconographer places his writing surface horizontally on a table in front of him, reflecting the heavens and the very face of God and His kingdom. I was not to create something new but to copy images that had canonical status in the church’s tradition and reflect the teachings of the Bible and the theology of the church. I was going to write like a scribe of old, copying the sacred texts of Scripture. In fact, an icon is often said to be read like a book since it proclaims a story, a sacred one, via an image.

I learned also that a beginning student in iconography always starts with writing an icon of an angel. Only after writing angels and many saints can the student move on to write the face of Jesus, for he, like his Father, is perfect. And what canonical angel did Vladislav give me to write? None other than the Archangel Gabriel himself. I would soon be tracing his image on a piece of wood that had been carved or routed. The routing creates a kind of frame in which to place the image, often with part of the image extending beyond the frame. Why? Because an icon can’t really be framed—it is not tame, to be held in place, but always wants to come out and claim the viewer for the kingdom.

An understanding of the material that goes into an icon is essential to grasp the spiritual stages and the symbolism of writing an icon. Only natural materials which once had God-given life are used. Vladislav said, “If we use dead things, things artificially made by man, then we put this artificiality, this death, onto the icon.” First animal or fish glue was applied on the board. Then comes gesso, a white chalk-like substance made from animal bones, which symbolizes the uncreated light of God. It shines through the image and thus becomes a bearer of and witness to the light of God.

After I traced Gabriel on the board, with a compass I created the nimbus or halo that encircles his head. To this area I applied bole, a kind of clay, that symbolizes the earth from which we were made. After hours of sanding the bole, I applied gold leaf to the halo to symbolize the Holy Spirit. Any imperfections in the sanding process became obvious when the gold leaf was applied, just as in our lives the coming of the Holy Spirit makes us aware of our deep imperfections, our sins. The gold is applied by taking deep breaths—again reminiscent of the Holy Spirit, the breath of God—drawing moisture from our lungs to warm the clay so it will receive the gold. It is then burnished and around the gold halo a line of red pigment called the Alpha ring is applied. This is the beginning of the process of applying pigments to the icon. At the end of the process, a white ring, the Omega ring, is added, marking the completion of the icon in God who is the A and the Ω.

The various colors of natural pigments, all ground to a powder, are mixed with the yolk of an egg and water and applied to the image by an ancient method called “floating.” I often referred to this watery process as the “flooding method.” The first pigments applied or “floated” on icons are coarse, gritty, dark colors. For the subsequent floatings—at least three of them—the pigments are increasingly finer in texture and lighter in color. Near the end, final highlighting is applied. It is remarkable to see what starts as the dark earthy green tones of the face eventually take on flesh. The fine lines that create the facial features are the most difficult to do, but when these are added, the icon comes to life. Then the name is given to the image, for God knows all of us by name, as we know Him.

At the very end of the process, slightly heated linseed oil is rubbed onto the board and miraculously the layers of pigments come together, giving the appearance of depth, as the uncreated light of God shines through the icon. This oiling process Vladislav likened to chrismation, the “seal that deepens us in God.” I followed the tradition for making a “real” icon by placing Gabriel on the altar in my church during a eucharistic service, where I silently prayed that the image would be a blessing to me and all who would see it. At that very moment, looking at the icon, I had the experience of looking through a window and what was on the other side—the kingdom of God—looking back at me.

I had two special experiences while writing my first icon. When I started to do some of the final lines on the face of Gabriel, I began to think how beautiful the image I thought I had created was. I am sure I had an expression of great delight on my face. Vladislav noticed this, my pride, and said, “Fred, I want you to float Gabriel with the dark gritty pigments with which you started and begin all over again.” Reluctantly, I did as he told me, and it was to me like God was covering my sin of pride. But in the end, as Vladislav knew, the more layers of pigments, the more beautiful the icon would be. In the writing of icons you never go back to correct errors, but instead you cover them. In life you can’t go back and live an experience over again, but through God’s grace the experience can be transfigured and, as with the icon, our lives can become more beautiful through the forgiveness of sins. In the words of St. Paul, “Blessed are those whose iniquities are forgiven and whose sins are covered” (Romans 4:7, and also Psalm 32:1).

My second unforgettable experience came when Vladislav checked my icon very near to its completion. He looked puzzled, confused, and finally said in stuttering, broken English, “The face! This Michael? No, Gabriel? Color right, wrong? Face wrong way!” and then after a pause, “Ah, a Lutheran Gabriel!” I don’t know if he knew from the beginning that I was doing Gabriel looking in the wrong direction, but I did learn that on an iconostasis in an Orthodox church, Mary, the saints, and yes, even the angels have a fixed direction from which they look at Christ who is in the center. The Archangel Michael always looks right and Gabriel always looks left, and I had reversed it. I was deeply grateful Vladislav did not tell me to do Gabriel all over. He did, however, ask me to do the Archangel Michael as my next icon—I certainly was not ready to move on to one of the saints or Christ—but with Michael maybe looking also in a “Lutheran” direction. Perhaps it would be the beginning of a future Lutheran iconostasis.

Writing the Archangel Michael taught me how important details are in an icon. The colors of the garments and the mixture of pigments that go into creating a color, the gestures of the body and hands that an angel or saint makes, what they hold in their hands—all these things are traditional. As Western religious paintings over time and even Eastern icons have lost these details, they have consequently lost some of their theological meaning.

Since writing that first icon of Gabriel, I have come to see that icons of Christ, angels, saints, and the major feast days of the church are treasures that can assist us in our life of daily prayer. When I was a child my mother taught me that when you pray you fold your hands, bow your head, and close your eyes. But I now see the value of having our eyes open in prayer and some area of the home or office set apart as a special place to behold an icon of the season. A triptych with three icons joined or even a small portable iconostasis can be taken when traveling. Such images can remind us that we are surrounded by a host of saints, living and dead, who join us in prayer. For most of the two thousand-year history of the church, images and pictures have been a part of entering fully into a life of prayer. What is really rare and alien are plain walls, the absence of color, and closed eyes.

I have also come to see the great value in icons bringing to us through lines and color a text that can be “read” by our eyes. Often in a sermon I would point to one of the two large icons I had hanging on the left and right sides of the arch separating the nave from the chancel in my parish. One of the images was always the same—St. Matthew, the patron saint of the church—but the other changed with the seasons of the church year and feast days. I referred to this icon to highlight the subtler theological expressions in the image. I would also sometimes take a smaller icon I had on the altar to share with the children during their sermon.[1]

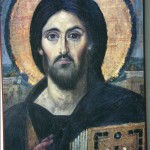

Finally, icons have a moral and ethical dimension. We were created in the image of God, in His image He made us, but the image is marred by our rebellion and sin. However, that image can still be seen unblemished in the icons of Christ, like the Holy Face of God icon and Christ Pantocrator. From the earliest times, iconographers of Christ have captured a face that is human and yet spiritualized with exaggerated features filled with symbolic meaning.[2] In the Christ Pantocrator image, Jesus has large eyes with which to behold God, but one of them appears larger than the other because of the way the one eyebrow is raised. This symbolizes that as God, Christ knows all, but in the flesh he was limited. He has a long thin nose, expressive of patience and gentleness, with the lines of the nose reaching up to the eyebrows to form the shape of a palm tree, symbolic of eternal life. He has large lumps or growths on the forehead, symbolizing the wisdom of God, and a large neck, symbolizing the breath or Spirit of God. He has small lips symbolizing one who is not a gossip and who takes no thought of what he shall eat or drink but seeks first the kingdom. In some images he has large ears to hear God speak. Jesus’ right hand is raised in blessing and the fingers are shaped to form the four Greek letters used in the abbreviation for “Jesus Christ”: I C Χ C. The early fathers of the church said that God has given people just enough fingers on each hand to spell His Son’s name.

When we look at the face of Jesus in iconography and then at those of his saints, we cannot miss the resemblance. Through these images we have ingrained in us that those justified by God’s grace through faith are sanctified and called to holiness of life. So in using icons in preaching I sometimes ask the people whether, in the years that have passed since they were claimed by the triune God in baptism, their noses have grown symbolically any thinner with patience and gentleness. Have they developed the lumps on their foreheads that signify wisdom? And pointing to the hands of saints like Luke and Nicholas forming the letters of Jesus Christ, I ask if they are “always ready to give testimony to the hope that is within you” (i Peter 3:15). In short, we are called to return to our baptisms daily, to die to sin and rise to newness of life, and to grow in the image of Christ and the fullness of his stature. Yes, we are justified by faith in Christ, but the justified life is instantly “clothed with God’s righteousness” (Romans 13:14) and marks the beginning of sanctification (Galatians 4:19 and Ephesians 4:14–16). I like to call this “iconic catechesis.”

When in the summer of 1991 I began to compile and edit the For All the Saints prayerbook, I knew that icons had to be included.[3] So in addition to daily readings from the whole word of God, and the writings and prayers of the saints from all the traditions of the church catholic, fourteen reproductions of icons of the Eastern church were included. I found a precedent for this in Luther’s prayerbook of 1529 where he reproduced fifty woodcuts illustrating the Scriptures from creation to the last judgment. There he wrote, “Even as God’s word is sung and said, preached and proclaimed, written and read, illustrated and pictured, Satan and his cohorts are always strong and alert for hindering and suppressing God’s word.”[4]

At retirement, I never fulfilled Gabriel’s word from the Lord in my dream to become an iconographer. However, my decision to study under Vladislav and later his two sons, Dmitri and Nikita, has helped me greatly in my own prayer life, in appreciating the value of icons in the Byzantine-Russian tradition of the church catholic, in using icons in preaching and teaching, and in introducing the icon through For All the Saints to many pastors and laypeople in the Lutheran church and beyond. One of the saints, John of Damascus, was once asked what he believed. He said, “Let me take you to my church and show you the icons.” I wish I could do the same.

Frederick J. Schumacher is the Executive Director of the American Lutheran Publicity Bureau. This essay originally appeared in Lutheran Forum, VOL 46/1 (Spring 2012): 61-64. Permission to use in this publication in “Let’s Talk” granted by the American Lutheran Publicity, Delhi, NY.

Notes

- See Frederick J. Schumacher, “St. Luke, The First Iconographer,” Lutheran Forum VOL 40/3 (Fall 2006): 6–8; “The Icon of the Nativity of Our Lord,” Lutheran Forum VOL 40/4 (Winter 2006): 6–9; “The Icon of the Resurrection of Our Lord: The Descent into Hell,” Lutheran Forum VOL 41/1 (Spring 2007): 4–8; “The Icon of the Visitation,” Lutheran Forum VOL 41 /2 (Summer 2007): 4–8.

- The earliest image of Jesus is preserved in a wall painting in the Catacomb of Commodilla in Rome and dates from the mid-fourth century. The earliest icon of Christ Pantocrator is from the sixth century, written in Constantinople and brought to St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mt. Sinai by Justinian. There may be a connection between these images and the legend in the Eastern church of an image given by Jesus of himself to King Abgar of Edessa and the legend of the Veil of Veronica (which means “true icon”) in the Western tradition.

- See the reasons that influenced the inclusion of icons in For All the Saints: A Prayer Book for and by the Church, vol. 1, eds. Frederick J. Schumacher and Dorothy Zelenko (Delhi: American Lutheran Publicity Bureau, 1996), vii–viii, xvii.

- Luther’s Works, American Edition, 55 vols., eds. J. Pelikan and H. Lehmann (St. Louis and Philadelphia: Concordia and Fortress, 1955ff.), 43:42–43.