We have used Lucas Cranach’s portrait of Martin Luther in a silk screen version as the logo for this Reformation 500 Jubilee issue of Let’s Talk. So much of the portraiture of the reformers and scenes of early Lutheran worship comes from Cranach that I thought he deserved some recognition in his own right.

When it comes to the arts associated with the Reformation music has pride of place. Martin Luther was himself musical and was a friend and admirer of leading composers of his day. But if it is true that “he who sings prays twice,” it is also true that “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Luther’s German Bible was studded with woodcut drawings from the Cranach Workshop in Wittenberg. Cranach left us portraits of Luther from different periods in his life and the only portrait we have of Katherine von Bora Luther. He was a friend of the Luthers and they served as godparents for one another’s children.

Cranach named himself after his hometown of Kronach, near Bamberg. He probably received his early training as an artist in his father’s workshop, although nothing is known about his father. Around 1500 he began traveling in the Danube valley, painting and making drawings for woodcuts. It is not known whether he met Albrecht Dúrer, whose workshop in Nürnberg was well known. But the evidence in Cranach’s paintings shows Dürer’s influence.

In 1504 Cranach was hired as a court painter to the Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony and in 1505 he settled permanently in the Ducal Castle in Wittenberg. We assume that his work had become known well enough for Cranach to land this prestigious position. His life was closely connected with the Saxon electors for half a century (1505-1553). He accompanied Frederick and his successors on hunts, travels, diplomatic missions, as well as to public festivities, weddings, and funerals, etc. Court painters were something like official photographers today, capturing events and painting portraits of the electors, their councilors, wives, and ladies. He was also “loaned” by Duke Frederick to paint portraits of other notables, including the youthful future emperor Charles V. This occurred in 1508 when Cranach accompanied an embassy to the court of Emperor Maximilian I. Of artistic importance is that a visit to The Netherlands in 1509 brought him into contact with Dutch art and indirectly with the style of the Italian Renaissance.

As the demand on Cranach grew, he hired assistants in order to turn out the increasing number of paintings and woodcuts that were requested. He moved out of the castle into one of the largest houses in Wittenberg, which also served as his workshop. He provided room and board to some apprentices and also opened an apothecary since he needed to mix chemicals in producing paints. Cranach gained great esteem among the townspeople of Wittenberg who in 1537 and again in 1540 elected him as their burgomeister (mayor). He became closely associated with Luther and the German Reformers and provided portraits of several of them. Sometimes their faces were included in altar pieces. He showed them preaching and administering the sacraments. The altar piece in St. Mary’s City Church in Wittenberg shows Luther in his doctoral gown preaching to a congregation with the crucified Christ between them in the center of the painting and in the large panel above that the reformers as disciples of Jesus at the table of the last supper.

Of course, Cranach’s bread and butter work of portrait painting continued. In the second quarter of the 16th century, Cranach increasingly favored a style of over-refined mannerism suitable to the members of the elector’s court. This is especially noticeable in his depiction of the female nude, such as in his several paintings featuring Venus and Cupid, for whom the ladies of Wittenberg undoubtedly served as models. Court life had a predilection for erotic representation favoring classical scenes, but Cranach’s painting of nudes spilled over into his religious and philosophical art such as “Charity with Four Children” (1534) and “Christ Blessing the Children” (1535f). Children especially were often nude figures, including the Christ child nursing on the breast of his mother Mary. There was no prudishness among these early Lutherans.

In the Smalcald War that erupted after Luther’s death, the Emperor Charles V was victorious over the Lutheran princes. In 1550, the elector John Frederick was accused of treason by the emperor and sent into exile. Faithful to the House of Witten, Cranach followed the elector in his exile at Augsburg, Innsbruck, and Weimar. Charles V remembered Cranach painting him as a youth and the artist pleaded with the emperor to treat the exiled elector as befit his dignity, Cranach died in Weimar in 1553 attending the exiled elector. Of three sons who followed him in the Cranach workshop, the second, Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515-1586), painted so like his father that their works are difficult to distinguish.

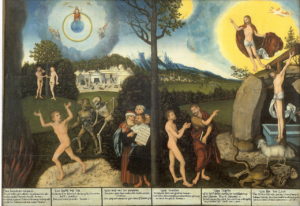

One of Cranach’s most unusual paintings was “The Allegory of Law and Gospel” (sometimes called “The Allegory of Law and Grace”) painted in consultation with Luther in 1529. It is a pictorial demonstration of Luther’s basic theology, with six supporting biblical citations on the bottom. It was rendered both as a woodcut and as a painting.

The picture is divided by a tree which is dead on one side (the law side) and blooming on the other side (the gospel side). In the upper left Christ sits in judgment on Adam and Eve as they eat the forbidden fruit. In the foreground a naked frightened man is forced into hell by a skeleton and a demon while Moses and the prophets hold up the Law. The Law cannot save the sinner from death and the devil. On the gospel side John the Baptist points the naked man to the crucified Christ (“Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.”). The risen Christ stands above the empty tomb in triumph over sin, death, and the devil. Our salvation comes not from the Law but from the death and resurrection of Christ.

Man is always naked before God who sees us as we are stripped down to our soul—a sinner in need of salvation, which only comes through the saving work of Christ. If a picture is worth a thousand words, this painting by Cranach makes Luther’s theology plain to anyone who looks on it.

The theological motifs in his paintings are sometimes more subtle than this. For example, his crucifixion scenes are sometimes more interesting in terms of the attitudes and reactions of the people below the cross than the figure of the crucified itself.

By his art Lucas Cranach the Elder was one of the great figures of the Reformation. The Cranach workshop (father and son) bequeathed to Lutheranism a heritage of devotional and instructional art that we have not maintained as well as we have preserved the tradition of church music. We are not edified by kitsch or sloganeering banners. We need art that draws us into the biblical story and prompts us to consider our own situation coram Deo.