- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

The LORD said to Satan, “Where have you come from.”–Job 1:7a. (NIV)

I was teaching a Bible study on the Book of Job. This was to be part of a longer series on Wisdom Literature. A readers’ theater version of chapters 1, 2, and 42 was presented in the second class. Various roles were assigned at random. In all, nine parts were given out. As the reading progressed, the person who spoke for the “LORD” spoke in an altered voice. It reminded me of an actor in a Greek tragedy speaking through a mask.

In some ways Job is the Hebrew counterpart to the Greek tragedy. One can readily imagine the LORD, Satan, Job, and his friends accompanied by a chorus of narrators. What sort of masks would be worn? I have an answer thanks to Archibald MacLeish and Ben Shahn.

I started my professional career teaching history and art history at a Pennsylvania college. I have always been fascinated by the influence of ideas, history and the arts upon each other. Truth be told, it is almost impossible to trace the origins of ideas and their expression in history or the arts. Nevertheless, it is fascinating to examine their intermingling. In the years since I left the academic world for seminary and parish ministry, I have often considered theology as part of this tapestry of thought and expression. This brings me back to Job and the voice of the LORD through a mask.

The Book of Job is the story of an upright and devout man who has his life thrown into chaos. He loses everything–his property, his children, and his own health. Why does this happen? Ask the LORD and Satan. This ancient fable posits the LORD as presenting Job as a truly righteous person. Satan maintains that Job’s devotion and righteousness is connected to his blessings. Fine, so take them away and see what happens. Job remains faithful. Even his wife tells him to, “Curse God and die.” This he will not do.

The friends who come to sit with him are initially silent. What can they possibly say? Well, it does not take them long to blame Job or blame God. In the end, the LORD kind of blows Job away with questions only God can answer. Every commentary, every book, every poem written on Job seems to come up with a different interpretation. Some conclude that God is at fault, and some deny the existence of the Almighty. Others uphold both Job’s righteousness and God’s justice. History, too, shapes these interpretations. The horrors of war have shaped our understanding of the Book of Job.

The poet Archibald MacLeish was one mid-twentieth century artist who gave voice to Job in J.B. in 1958. This “play in verse” won both the Pulitzer Prize for literature and a Tony Award for best play. MacLeish was responding to the horrors of war, the Holocaust, and Hiroshima. He turned to Scripture; as he writes in the foreword to the play, “When you are dealing with questions too large for you which, nevertheless, will not leave you alone,” the Bible is the place to seek a framework.[1]

The photographer, calligrapher, printmaker, painter and muralist Ben Shahn was also influenced by the horrors of war and the nuclear age. His early education in his native Lithuania (1898-1906) formed his worldview. He recalled that his days were spent ‘“learning the true history of things, which was the Bible; to lettering its words, to learning its prayers, and its psalms, which were my first music, my first memorized verse. Time was to me then, in some curious way, timeless. All the events of the Bible were, relatively, part of the present.”’[2]

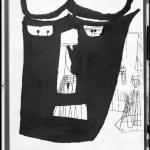

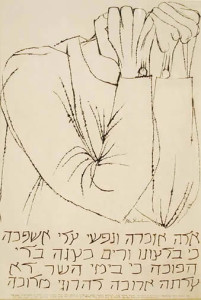

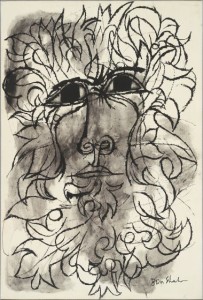

Shahn worked as part of the New Deal artists’ projects during the Depression years. During World War II, he worked with the Office of War Information. During these years his work evolved into a style “more private and inward looking: ‘A symbolism which I might once have considered cryptic now became the only means by which I could formulate the sense of emptiness and waste that the war gave me, and the sense of the littleness of people trying to live on through the enormity of war.’”[3] A later work, Warsaw 1943 (Figure 1), displays the stark emptiness of the atrocities of war. The Hebrew calligraphy is a prayer taken from the Musaf Service for Yom Kippur. It reads in part, “These martyrs I well remember, and my soul melts with secret sorrow. Evil men have devoured us and eagerly consumed us….”[4]

Both Archibald MacLeish and Ben Shahn are deeply moved by the atrocities of war. It was, perhaps, inevitable that these two artists, who were also bound by their devotion to biblical imagery, should collaborate in the production of a work that is developed from the Book of Job. MacLeish’s play, J.B., calls for masks for God and Satan. The characters Mr. Zuss and Nickles speak:

Nickles: You’ll play the part of…

Mr. Zuss: Naturally!

Nickles: Naturally! And your mask?

Mr. Zuss: Mask?

Nickles: Mask. Naturally. You wouldn’t play God in your Face would you?

Mr. Zuss: What’s the matter with it?

Nickles: God the Creator of the Universe?

God who hung the world in time?

You wouldn’t hang the world in time

With a two-days’ beard on your chin or a pinky!

Lay its measure! Stretch the line on it!

Later, in answer to Mr. Zuss’s continuing protests, Nickels replies:

But this is God in Job you’re playing:

God the Maker: God Himself!

Remember what He says?–the hawk

Flies by His Wisdom! And the goats –

Remember the goats? He challenges Job with

them….[5]

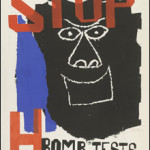

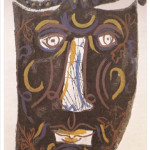

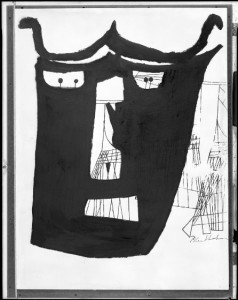

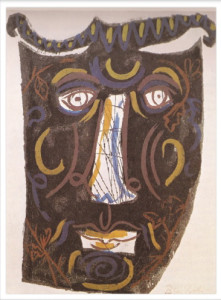

MacLeish asked Shahn to design masks for God and Satan. The stage setting describes the God mask as, “…a huge white, blank, beautiful, expressionless mask with eyes lidded like the eyes of the masks in Michelangelo’s “Night”. Satan’s mask, by contrast is, “large as the first but dark to the other’s white, and open-eyed where the other was lidded. The eyes, though wrinkled with laughter, seem to stare and the mouth is drawn down in agonized disgust.”[6]

The masks designed by Ben Shahn capture the power and the mystery of these other-worldly antagonists. (Figures 2 and 3). “The first God face…might have been that of Zeus or some other archetypal image of a god; or it might have been any of those bearded mythic faces that preside over Roman doorways and drinking fountains.” A later “metamorphosis” of the companion mask is thus explained: “Ben painted the Satan in stark black and white, keeping the double-pupiled eyes and other curiously haunting and disconcerting details of the original.”[7]

However, I also include an image of the 1959 mask commonly clued “JB’s Blue Satan” (Figure 5). This is the way the mask was shown in The Collected Prints of Ben Shahn, by Kneeland McNulty (1967). I have not been able to discover if the mask-maker, James Kearns, used this version or the plain black and white one for the original production. Ben Shahn produced much of his work in both black and white and color since he was primarily a graphic artist. The sculptor, James Kearns, cast the masks into three-dimensional works in several materials, including bronze and iron. Shahn treasured the iron and papier-mache masks made by Kearns.[8]

The actors are transformed by their masks. “Their voices, when they speak, are so magnified and hollowed by the masks that they scarcely seem their own.”[9] At one particularly contentious point, the stage directions state: “They put their masks on fiercely, standing face to face. The platform light fades out. The spotlight catches them, throwing the two masked shadows out and up. The voices are magnified and hollow, the gestures formal…”[10]

In the spotlight they are larger than life. And there is more. It happens for the first time as the Prologue draws to a close. “A Distant Voice” comes out of the silence, “Whence comest thou?” In the end it is the “Distant Voice,” not Mr. Zuss in the God mask, who responds to J.B.’s lament.

Who is it that darkeneth counsel

By words without knowledge?…

Where wast thou

When I laid the foundations of the earth…

When the morning stars sang together

And the sons of God shouted for Joy?[11]

The biblical story and its voice take over and the actors never quite understand that.

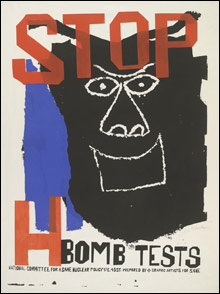

So it was for the artists who gave Job new meaning in the mid-twentieth century. Ben Shahn’s Satan mask appears later as the personification of evil on an anti-H Bomb poster. (Figure 4). The God face took on more splendor, “executed in many shades of yellow in the painting, When the morning stars… with the words of God’s rebuke to Job lettered in gold-leafed Hebrew characters.”[12] They became more universal symbols of evil and benevolence.

Harold S. Kushner has offered an insight into MacLeish’s later views on J.B. and the Book of Job. Rabbi Kushner cites a 1967 sermon given by MacLeish at his church in Farmington, Connecticut. The key passage is: “‘Man depends on God for all things; God depends on Man for one. Without Man’s love, God does not exist as God, only as Creator, and love is the one thing no one, not even God, can command….Acceptance of God’s will is not enough. Love, love of life, love of the world, love of God, love in spite of everything is the only possible answer to the ancient human cry against injustice.’”[13]

These may or may not be our interpretations of the Book of Job. The artist, the poet, the philosopher are outside the bounds of creed. Ben Shahn writes: “If the artist, or poet, or musician, or dramatist, or philosopher seems somewhat unorthodox in his manner and attitudes, it is because he knows–only a little earlier than the average man–that orthodoxy has destroyed a great deal of human good, whether of charity, or good sense, or of art.”[14]

We started with a Bible study and now there has been a sermon. A poet and an artist and even a rabbi have had their say. The masked-mystery remains somewhere in the distance, yet increasingly near. The challenge remains for the preacher, the teacher, the poet, and the artist of the 21st century to keep telling the tale. Does the God of the Book of Job speak to our time? Does God remain hidden in the attacks of terrorists? Is Job a parable for Chicago’s families who continue to lose children to gun violence?

May we return to Figure 1, Ben Shahn’s Warsaw 1943? It could easily be renamed “Chicago Neighborhoods 2013.” The sense of grief and despair is timeless. Let this image reach into our time and tell the story. Let Father Pflager prophesy. Let Mayor Emanuel call for justice. Let someone new write the play. Let someone new paint the picture. Let love overcome.

A distant voice is heard, “I am with you always.” The curtain falls. The play goes on….

Notes

- J.B. A Play in Verse, Archibald Macleish, Samuel French Inc., p. 6.

- The Complete Graphic Works of Ben Shahn, Kenneth W. Prescott, Quadrangle/the New York Times Book Co., 1973, quoting, Love and Joy About Letters,Ben Shahn, 1963.

- Ibid., p. xix.

- Ibid., p. 51.

- J.B., Archibald MacLeish, Houghton Mifflin CompanyBoston, pp. 16-17.

- Ibid., pp. 16 and 18.

- Ben Shahn, Bernarda Bryson Shahn, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., p. 216

- The Complete Graphic Works of Ben Shahn, p. 41.

- J.B., Houghton Mifflin, p. 21.

- Ibid., p. 50-51.

- Ibid., p. 24 and 128

- Ben Shahn, p. 216

- The Book of Job, Harold S. Kushner, p. 192.

- The Shape of Content, Ben Shahn, Vintage Books, p. 28.